I began writing The Goji Project the summer after I graduated high school. I had just learned about Neil Bostrom’s simulation theory and was really intrigued by the idea. I had an idea for a short film about the theory that used framing and focal length to make characters feel real or simulated. I wrote a basic story outline that contained the foundations of The Goji Project focused around this idea of focal length, but I put it away and didn’t think about it for years afterwards. In the meantime, I went to college, working on a degree in Advertising.

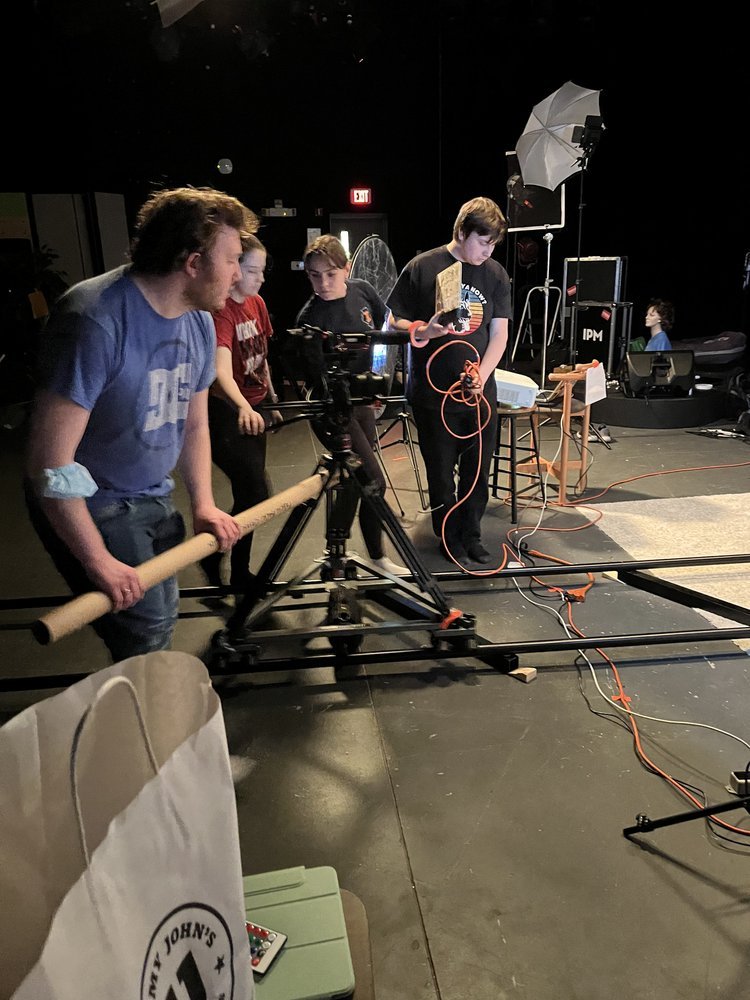

The set of The Goji Project. A projector is playing news footage at a reflector to create a TV-light effect.

I made videos when I could, but for the most part I learned how to be a creative advertiser. I started doing headshots, grad photos, music videos, and weddings. But I realized very quickly that I wasn’t feeling entirely fulfilled with that type of creative work. I wanted to get back to short films. I returned to Chicago for the summer and began working on expanding Whitewater, a short film that I had made in high school, into a short feature. Little did I know that students don’t make short features because they’re very difficult to do - we shot the project that summer but never completed it. The pandemic hit not long after that. I arrived at my senior year with a lot of video experience, but nothing I felt that I truly owned.

I decided that I wanted to produce a short film before I graduated to prove to myself that all the technical skills and creative sense that I had learned could be lent to a career in cinematography. I had already taken the capstone film class, but I petitioned the university to let me take the class again. My petition was accepted, and my professor, Victor Font, accepted my script to be produced as part of the class.

I cut most of the characters from the original plot and completely reworked it, learning from my past failures and trying to write a movie that could be easily produced by students with what resources I had. I drew a lot from my experience during quarantine, and the thoughts that often consumed me while I was trapped at home with nothing to do but watch the world. I started focusing on themes of existentialism and finding meaning in the world. The story began to take on dimension.

Preproduction lasted two months, during which we scouted locations, gathered the costumes and wigs, made schedules and shot lists, and most importantly, built the apartment set. The set was built wooden flats, put together to simulate a two-walled bedroom. We put down carpet and baseboards, installed shelves and a curtain rod, and decorated the room, largely with items from my own bedroom. Most of the records on Goji’s wall came from my collection: a fun easter egg is that the album on the top right of her grid is Concessions by The Good, a band started by my dad Tony Rogers, who also did the score for this film.

We began production with a plan that we managed to mostly stick to. We had twelve days of principal photography which spanned a 6 week period. The very first shot of the film is a very slow dolly-in that immediately reveals the apartment set in its entirety, breaking any illusion that this room is real. I decided to start with this ultra-wide angle that shows the edges of the studio to call attention to the artificiality of Goji’s situation: she is literally waking up in a simulated apartment. I played very deliberately with dramatic lighting for the same reason. I liked the idea that Goji’s life felt like a play, a large and grand production that is almost completely empty except for her. My original focus on framing and focal length returned here, and I tried to push our wide shots as wide as possible, and our close shots as close as possible (I heavily relied on a 100m macro lens that allowed us to get really close detail).

We found out very quickly when we left the studio that it was a lot harder to plan our days when we had to contend with the weather. The second half of production was plagued with weather delays and cancellations. We shot at a lake one day, and it was so cold that our actors had blankets wrapped around them every moment we weren’t shooting. We used a big blanket (codename “The Wind Wall”) to block as much wind as possible, and even tried to fake sunset lighting by blocking the sun and re-lighting our actor’s faces.

As production wrapped up, we already had a deadline bearing down on us: the UIUC Film Festival was expecting a cut of our film in just a few weeks. I began editing very quickly, working with my dad on the score and doing sound design. The majority of the foley was recorded in my apartment. I pulled an all-nighter the night before the festival deadline, but I walked into class the next morning with a finished movie on a hard drive.

I created posters and flyers to promote the film. We booked a venue and held a full-on premiere event, complete with a panel with the filmmakers and actors afterwards. Over 100 people attended our event, after only a week of promotion. The film was received very well, and was shown again in the UIUC Film Festival that night. We went on to receive numerous film festival awards, including a nomination for “Best Sci Fi Short” at LA International Film Festival’s Indie Short Fest.

The Goji Project is something I am incredibly proud of, not just because I feel good about its technical quality, but because of the experience that I had making it and the people that shared that experience. The crew of MACS 480 was absolutely committed to making this project great, and I wouldn’t have been able to do it without them. Filmmaking is a team effort, and I am grateful to have shared it with such hardworking friends.